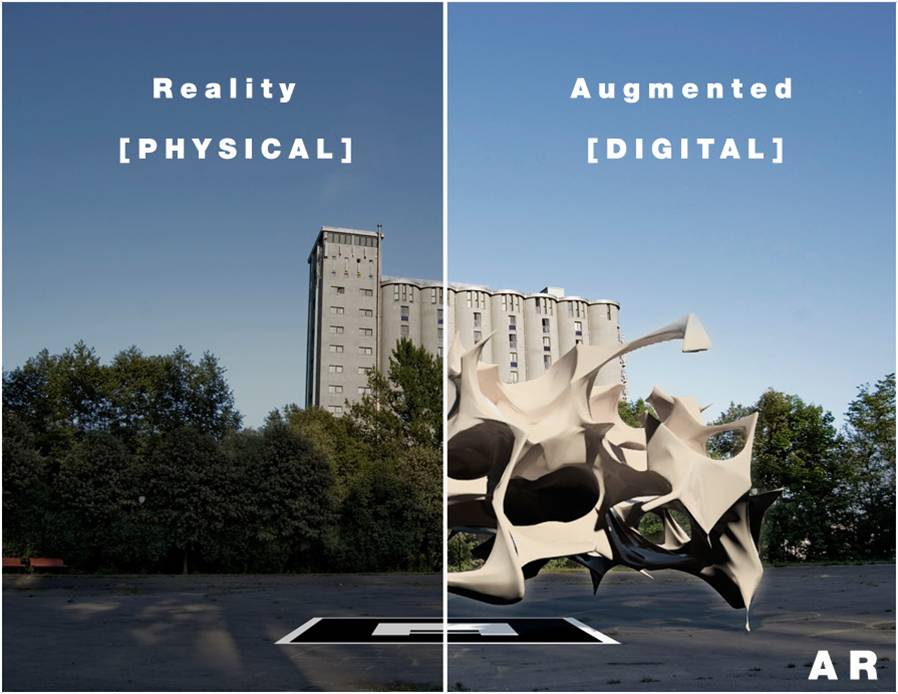

Whether or not you understand the recent drive to fill the world around you with obnoxious animated characters that you can only see as long as you hold your phone up in front of your face at all times,augmented reality does have the potential to enhance our world in ways that are occasionally useful. However, the AR experience is currently a sterile one, with augmentations overlaid on top of, but not really a part of, the underlying reality.

Abe Davis is a graduate student at MIT Rather than using 3D graphics to model the motion characteristics of objects, IDV extracts motion information from a small amount of 2D video, and then generates simulations of objects in that video, allowing the augmented part of AR to interact directly with the reality part, turning static objects into objects that you (or your virtual characters) can play with.

To understand how this works, imagine a simple moving object, like bedsheet hanging on a clothesline in a gentle breeze. As the wind blows, the sheet will ripple, and those ripples will consist of a horizontal component (movement across the sheet) as well as a vertical component (movement up or down the sheet). Once you’ve figured out these motion components, called resonant or vibration modes, you can simulate them individually or combine them together in ways that can mimic a breeze blowing in a different direction or at a different strength. The fundamental knowledge that you gain about how the real sheet moves on a very basic level allows you (and a real-time video editor) to make the sheet in the video move in a realistic way as well, without being constrained by reality itself.

This method can be applied to much more complicated objects than bedsheets, although it gets trickier to pick out all of the vibration modes. For it to work properly, you need a stable, baseline video of the scene, you need to move the object that you’re interested in simulating, and you need to watch it move for long enough that you can accurately extract the vibration modes that you care about, which may take a minute or two. Unfortunately, this means that using it for Pokemon GO is probably not realistic unless you have a lot more patience and restraint than the typical Pokemon GO player seems to have, because you can’t just wander around and point your phone at physical objects that can be instantly animated (yet):

As curmudgeonly as we are about whatever silly games kids (and some adults) are playing these days, the underlying technology here is very cool, and there’s potential for many different applications. Generally, modeling a real world object for any purpose, from civil engineering analysis to making animated movies, requires first making a detailed 3D model of that object and applying a physics engine to get it to move. With interactive dynamic video, you can skip the complicated and time-consuming 3D modeling step to create a virtual model with reality-based physics. Such a model may not offer the same movement space as a full 3D model, but that’s a reasonable trade-off for only having to spend a minute or two with video camera and a tripod to create it.

While Davis has no immediate plans to commercialize any of this (he’s heading to Stanford for his postdoc in the fall), MIT has a patent on the technique, and it’s not difficult for Davis to speculate about where we might see IDV in the near future.

“[W]hen you look at VR companies like Oculus, they are often simulating virtual objects in real spaces,” he says. “This sort of work turns that on its head, allowing us to see how far we can go in terms of capturing and manipulating real objects in virtual space.”